“A nation cannot be built on fear. A people cannot be governed by guns. Let us remove the steel from our hands so that trust may return to our hearts.”

Abstract

This article contends that the emergence of today’s Somaliland National Army — and, by extension, Somaliland’s very survival as a political order — cannot be explained solely by institutional design or peace negotiations. Rather, Somaliland’s transition from armed pluralism to statehood hinged on a single foundational act: the voluntary, first-mover disarmament of the Arab (Arap) clan under Sultan Mohamed Sultan Farah in early 1994. Through a close reading of the disarmament process and eyewitness quotations, this study shows how Sultan Farah’s moral authority transformed fear into trust, enabled the surrender of weapons without coercion, and made possible the consolidation of a national military force. Without this intervention, the logic of mutual fear would likely have persisted indefinitely, precluding the formation of today’s Somaliland National Army and, with it, Somaliland’s survival as a functioning polity.

Introduction

On 2 February 1994, what would become the Somaliland National Army Day unfolded at Hargeisa Stadium not as a mere ceremony but as a defining political act. Militia units from the Somali National Movement (SNM) — including the distinguished Sancaani Brigade — handed over weapons to the nascent government. This moment marked the beginning of the transition from clan-controlled arms to a unified national military. Yet this transfer did not occur through coercion or external guarantees. It occurred because one leader chose to act where others hesitated.

This article argues that without Sultan Mohamed Sultan Farah of the Arab (Arap) clan, Somaliland would not exist today in anything resembling its current form. His decision to initiate disarmament reshaped the political landscape, making possible a national army and the sovereign authority it supports.

Post-Liberation Security Dilemma: Independence without Control

After the fall of the Somali Republic in 1991, Somaliland declared independence and emerged from war with fragile unity but deep insecurity. Weapons remained distributed widely among clan-based militias. Every community recognized that peace required disarmament, but no group was willing to move first. The logic was simple and brutal: disarm first, and risk annihilation.

The newly elected government under President Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal had moral authority but no monopoly on force. There was no army to command, no police to enforce order, and no external peacekeeper to guarantee security. Disarmament was repeatedly acknowledged as necessary, yet not a single clan was willing to take the first step.

In this context, fear ruled. Political speeches, religious appeals, and consensus statements repeatedly concluded with the same outcome: “not yet.”

Sultan Mohamed Sultan Farah and the First-Mover Problem

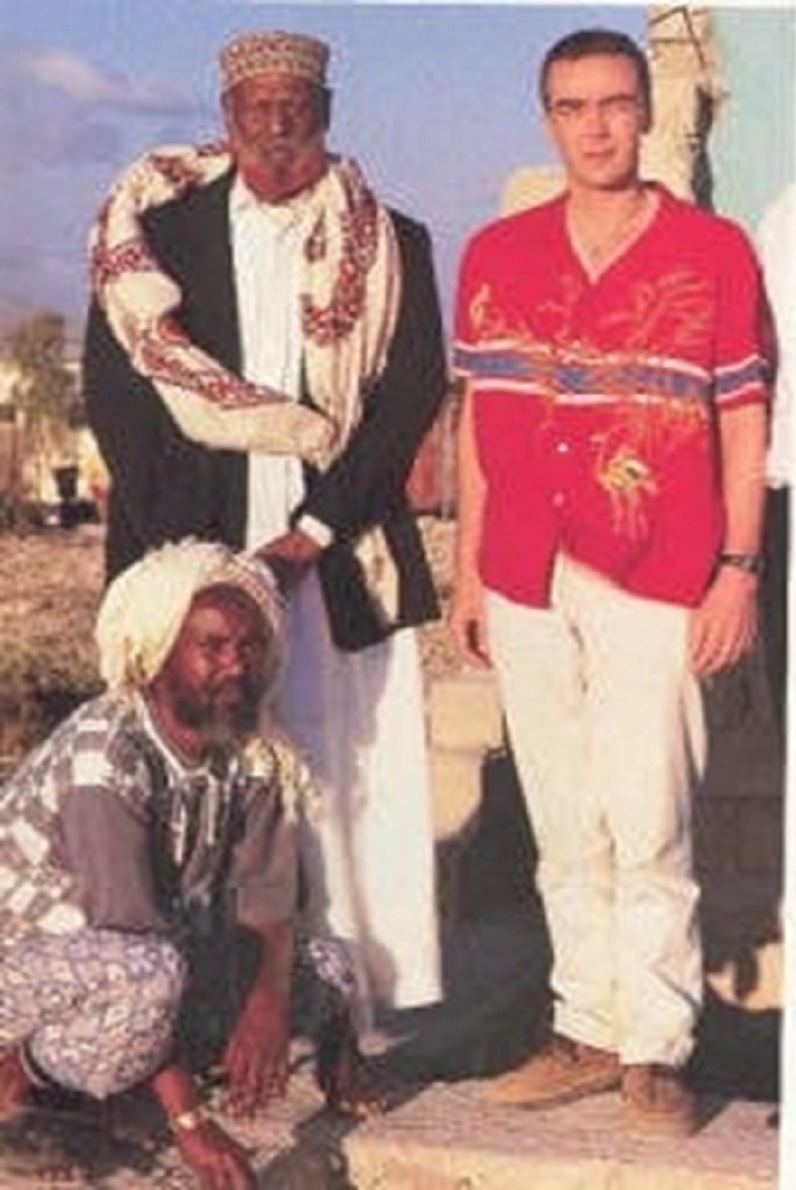

Sultan Mohamed Sultan Farah’s authority was rooted in lineage, mediation, and longstanding respect across Somaliland. As the overall Sultan of the Arab (Arap) clan and an early supporter of the Somali National Movement, his influence transcended ordinary customary authority. Where political leaders were constrained by institutional weakness, he possessed the moral capital to act first.

At a key Borama meeting in January 1994 — convened to address disarmament — discussions stalled once again. Elders and commanders acknowledged the necessity of disarmament, but each insisted that others should go first.

It was in this atmosphere that Sultan Farah spoke:

“A nation cannot be built on fear. A people cannot be governed by guns. Let us remove the steel from our hands so that trust may return to our hearts.”

This statement did not demand obedience; it invited courage. As recounted by Haji Cabdi Waraabe, Sultan Farah followed it with an unprecedented pledge:

“The Arap clan will disarm first.”

For a brief moment, the room was stunned. No clan had ever declared such a willingness to take the first step. Sultan Farah was not asking for assurances, nor promising guarantees from others. He was offering trust without conditions — a radical inversion of the logic that had paralyzed Somaliland since the war’s end.

Disarmament as a Moral and Political Act

Sultan Farah’s words mattered not simply because they were eloquent, but because they were credible. He did not rush to command; he spoke after years of service, mediation, and demonstrated commitment to collective survival. His moral authority was the resource that allowed him to transform fear into a political possibility.

Returning to Baligubadle, Sultan Farah convened a grand clan assembly — inclusive of elders, former fighters, youth, and religious leaders — to explain the proposal and secure genuine consent. Speaking plainly about the stakes, he addressed the central fear:

“We will disarm not because we are weak, but because we are strong enough to trust ourselves.”

When his people raised practical fears — “Other clans will attack us,” “We will be defenseless,” “This is a trap” — he did not dismiss them. Instead, he offered a moral boundary around violence:

“If anyone attacks you, they must face me first. And if they attack our clan, we will take their weapons as our only response.”

This was neither a threat of revenge nor a promise of dominance. It was an assurance that strength would be used to end violence, not perpetuate it. In that moment, the psychology of fear began to shift. Disarmament became an act of honor rather than vulnerability.

2 February 1994: From Clan Arms to a National Army

On 2 February 1994, the formal disarmament ceremony at Hargeisa Stadium became the birth event of the Somaliland National Army. The Sancaani Brigade — among the SNM’s most experienced units — voluntarily handed over weapons, including rifles and artillery, to the government. This was more than a procedural transfer; it was a public affirmation that the state, not clans, would henceforth hold legitimate force.

At the event, Sultan Farah declared:

“Our clan will be the first to disarm. Whether medals are awarded or certificates are given, we will lead the way.”

The stadium responded with celebration, and President Egal honored Sultan Farah and the Arab (Arap) clan with medals, recognizing the courage and precedent set by their decision.

President Egal later reflected:

“Sultan Mohamed built the nation with one act of courage. He gave Somaliland its future.”

This was not mere rhetoric. It was a recognition that the army was born the day weapons were surrendered without coercion, and that surrender was made possible by Sultan Farah’s moral decision.

From One Act to National Transformation

The Arab (Arap) clan’s disarmament triggered a cascade effect. Other clans followed, not because they were compelled, but because the meaning of honor and legitimacy had shifted. Disarmament became a symbol of moral strength, not weakness. Weapons ceased to be primary sources of security; trust and shared commitment became the currency of peace.

Within months, the majority of SNM fighters had demobilized, heavy weapons were surrendered, illegal checkpoints disappeared, and roads reopened. As armed authority consolidated, conversations shifted from survival to organization: policing, coordination, civilian authority.

The Somaliland National Army did not emerge simply as an institution; it emerged as a social contract grounded in voluntary restraint.

Conclusion

The existence of today’s Somaliland National Army — and the relative peace and stability that characterize Somaliland — rests on a pivotal causal sequence driven by one leader’s decision. Sultan Mohamed Sultan Farah’s willingness to absorb risk and place his own people at the forefront of disarmament transformed a deadlocked society into a state capable of governing itself.

Somaliland was not made solely through declarations or conferences. It was made in 1994, when one leader chose to lower arms first and ask others to follow — invoking trust where there was fear, and imagining a nation where there was fragmentation.

On this 32nd anniversary of Somaliland National Army Day, that foundational act remains the moral and political bedrock of Somaliland’s development and progress.

Without Sultan Mohamed Sultan Farah’s courage, there would be no Somaliland National Army. Without that army, there would be no Somaliland today.

Gulaid Yusuf Idaan

Independent Researcher

Specialist in Conflict Resolution, Disarmament, and Horn of Africa Politics